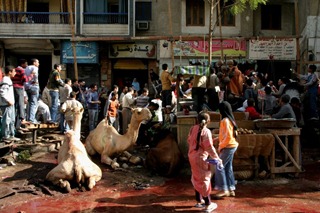

(** GRAPHIC MATERIAL! / ATTENTION IMAGES VIOLENTES **)

Monday the 8th of December was the start of Eid el-Kibir (the “big festival” in the Egyptian dialect, though also known as Eid al-Adha in other Arabian dialects meaning “festival of sacrifice”). Considered the most important celebration in Islam, it comes roughly seventy days after the end of the month of Ramadan in correspondence with the end of the hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca). It is a festival in remembrance of Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his own son to Allah. Just as Allah intervened with Abraham, offering a ram in place of his son, it too is the tradition in Islam to have an animal slaughtered for the feast (usually a sheep, but may be a cow, camel, or goat). The city shook with nervous excitation for the weeks leading to the events of the next four days.

All persons must attend first prayers on the morning of Eid el-Kibir, usually in their finest clothing. Young and old women flooded the shopping centers the week before the festival for the newest styles and cuts. Men and young boys could be seen pulling bucking rams hastily from the trunks of their cars and from the tops of their bicycles, marked in pink paint to assure it was their choice from the flocks. Islamic law demands that every animal purchased must be sectioned into three even piles of meat: the first for the families which cannot afford sacrificial meat for the festival, the second for relatives, neighbors, and friends (many of whom are also invited to the communal feasts of each household), and the third to keep. This is an active ethical institution in Muslim teachings that encourages the community wealth as a priority. The animals sacrificed must be of a strict set of quality, age and health requirements according to Islamic law.

I had been troubled preparing for the Eid el-Kabir, as to my own sensibilities regarding the killing of so many animals in the street. And as a vegetarian, how I would feel walking through the torrent streams of blood in the streets, the handprints of blood on the walls, cars, and faces (a symbol or good prosper and success), or to witness the murders themselves.

The first morning I was up at 4:45 AM to record the first prayers at 5:00. The streets were empty, with the exception of a few children laughing and running with about with the overwhelming anticipation of many children I knew as a child awaiting Christmas morning.

Eugénie and I and Aymon, and another anthropologist friend Hossam ambled the deserted streets in the morning. Many of Cairo’s citizens travel to the Red Sea or to Alexandria for the holiday. The city felt reflective and somber in wake of it’s coming celebration. There were no screaming beasts and bellowing crowds in the early hours of the day. There was your occasional puddle of red and excrement, but it was a noiseless remnant, a stain deep in meditation and thoughtful of its symbol. The scent of blood was strong and heavy in the air. The tapestries hung in prolific waves of color throughout the streets, often meant as barriers to protect the hanging meat from the sunlight. Children had left their handprints of blood covering entire walls of local businesses, places of worship, and residential home fronts; the freshest being red, the early-risers already chapped shades of waxen black.

Before noon, Eugénie and I headed in the direction of our beloved market of Sayeda Zeinab, where we had spent much time in the preceding days familiarizing and orientating ourselves with the vendors and streets. It was here we decided to focus our mid day energies, since the feast is served early in the afternoon, it was here that the freshest cuts would be made.

Above: Camel's feet / pieds de chameaux

The most difficult moments for me, and the gentle soul that I carry, was the spectacles of slaughter. Large gangles of singing/shouting ten-year-olds and their parents surrounding a large bull shouting “cut his throat”, drums in ecstatic assault, as Sabrir (“the most famous slaughterers in the quarter”) danced about like a Victorian charlatan with a handsome smile as he dexterously and efficiently swiped a large canyon in the throat, and the bull came tumbling after. We stood and watched as two more bulls, six sheep, and three gorgeous camels were quickly given the same joyous parting as the first. We stood nearly to our ankles in blood. The gang-like enthusiasm was an impression the likes of which I’ve never witnessed. I fought hard to understand that the symbol of the sacrifice was that of great humility to Allah as well, and was a prelude to the feast to follow.

Soon afterwards, the streets were all but empty again as each family retreated to their homes for intimate celebration. Throughout the early evening were children at play in the streets, and music from parked cars providing an ambiance of cheer to the neighborhood. My trauma subsided quicker than expected, and the rest of the first evening was spent having slow promenades and meaningful conversations with others as to their relationships with the day, and their love of the teachings of the Prophet. Eid el-Kibir was in fact a smaller festival than it’s name suggested to me, but one with more affection and sentiments of family than had been suggested to me. Most of all, I was still quite content to be a vegetarian at the end of it.

L’Aïd el-Kebir, la grande fête (عيد الكبير en langue arabe) aussi apellée fête du sacrifice est la célébration la plus importante de l’islam. Selon le calendrier lunaire, cette année l’Aïd el-Kebir a lieu le 8 décembre 2008.

La date correspond avec la fin du hajj, le pélerinage à la Mecque, soit environ 70 jours après la fin du Ramadan. L’Aïd el-Kebir commémore la soumission d’Abraham à Hallah quand Abraham accepte de sacrifier son fils pour ce dernier. Alors que le père s’apprête à égorger son fils, Allah accepte d’éxécuter un mouton pour sauver le jeune. Le mouton devient alors le symbole du sacrifice.

Bien qu’il s’agisse d’un important événement religieux, l'Aïd El Kebir est une grande fête familiale et sociale au cours de laquelle le partage est essentiel. Ainsi, l’indigent qui ne peut acheter de viande se verra invité à partager le repas. Les amis, musulmans ou non, sont aussi conviés.

En attendant l’Aïd

Les stands sont souvent tenus par les femmes, les hommes étant occupés aux travaux d’égorgement et de découpage des grosses pièces. De grands plateaux cabossés présentent entrailles et têtes. Dans des bassines flottent les intestins translucides soigneusement lavés à la main. Des pièces de viande pendent à des crochets. Les pattes des bêtes sont grattées au couteau pour retirer tous les poils, des chaussons de chameaux trainent partout sur le sol.

5 heures du matin, le muezzin ouvre la fête

La journée commence tôt aujourd’hui. A 5 heures du matin, le muezzin récite sa première prière. La veille la rue a été vidée de ses voitures et des tapis verts au couleur de l’islam ont pris la place. Dans la fraîcheur matinale, quatre adolescents jouent sur les tapis avant de faire une sieste religieuse. Le stand du marchand de foul a lui aussi été condamné. Les hommes commencent à se rendre à la mosquée et, quand cette dernière est pleine, on s’installe sur les tapis dehors. A 6 heures le jour se lève à peine et la rue est encore calme, seuls quelques hommes prient en silence. Une heure plus tard il ne reste plus de place sur les tapis, les hauts parleurs installés à l’extérieur de la mosquée diffusent des chants lancinants. A présent, des centaines de personnes reprennent en cœur les paroles du sheikh doublées par celles d’un enfant. Un bébé tente aussi de suivre le rythme, au premier Allah Akbar, il décroche et gazouille. Puis, la foule se dissoue dans les ruelles aux alentours, on range alors les tapis et la circulation reprend lentement.

La danse des chameaux

La veille trois chameaux dormaient, tranquillement installés sur une place près de chez nous. Nous passons au moment où c’est à leur tour d’être sacrifié. Un abattoir en plein air à été aménagé pour l’occasion. Déjà au loin on peut entendre la foule bouillonner. Sabrir, le tueur est très connu dans le quartier, il vient de saigner une vache et, glorieux il lève son couteau, la foule l’acclame.

Une fois rentrés à la maison on tape à la porte, une jeune fille voilée me tend un gros sac de viande encore chaude, c’est une voisine qui nous offre une part de sa vache. Notre hôte Aymon est ravi, il va enfin pouvoir cuisiner ce mouton bourguignon dont il rêve depuis quelques jours. L’esprit encore dans les entrailles, je penserai au festin un peu plus tard.

La fête de l’Aïd rime aussi avec début des vacances. Les enfants sont alors partout dans les rues. Dans chaque quartier ont été installées de petites fêtes foraines. Les petits tourbillonnent sur des balançoires qui grincent en rythme. Puis, tout le monde s’entasse sur une charettes tirée par un âne, c’est parti pour un tour de quartier à toute allure en chantant en coeur.